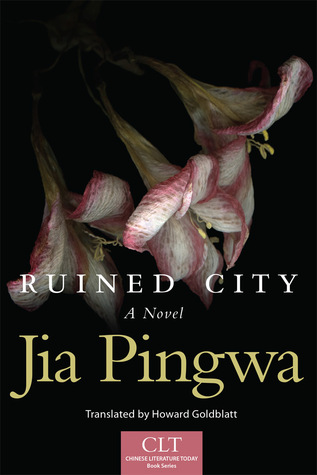

Translated by Howard Goldblatt, published by University of Oklahoma Press, January 2016.

Read a sample | Purchase on Amazon.com

“Through meticulous care in setting and character and by focusing on just a few intellectual celebrities as well as their wives, acolytes and enemies, Jia Pingwa builds a city from top to bottom for the reader. We learn its inner workings: its domestic life, bureaucracy, markets, and criminal underworld. From the lowliest junkman to the local mayor, we watch this city and its denizens gradually grow more amoral and more decadent in a short period of time. […] Almost no one in this novel is a hero or a villain-they’re mostly ordinary people trying to get by with the least possible effort for the greatest possible gain. While the reader may not ‘like’ or sympathize with any of these individuals, it’s also very hard to hate or judge them-they are too like people we might know (even people we might be). ”

– Marie-Therese, Goodreads

“The pacing of Ruined City isn’t like that in most contemporary fiction. It putters along and the action can seem limited, even inconsequential. It takes up different threads, and leaves characters out of sight — and grasp — for extended stretches, the focus not on what one imagines is the central story, but rather on the incidental. Even when things come to a head in a courtroom, Jia keeps his distance, preferring to summarize second-hand. It takes a certain kind of patience to read this kind of often pedestrian-seeming narrative, and the payoff may well not be sufficient for many readers. But in its sum Ruined City is also a powerful, ultimately even devastating work — a striking success. ”

– M.A. Orthofer, The Complete Review

“Like some of the classics of Chinese literature — The Water Margin, Journey to the West, The Dream of the Red Chamber, The Scholars — Ruined City has to be appreciated for its small pleasures as much as its larger themes: It’s a grab bag of techniques and vantage points, from the loving description of a living room filled with furniture imported from Hong Kong (a rare sight in the 1980s) to a passage seen from the perspective of a cow. […] While the Cultural Revolution is referred to in places, it’s clear that Jia wants his characters to seem neither traumatized by nor interested in politics. They live in a tiny world of their own making and seem — like artists everywhere — to thrive on life’s small dissatisfactions. That may be the novel’s most shocking quality of all.”

–