Background

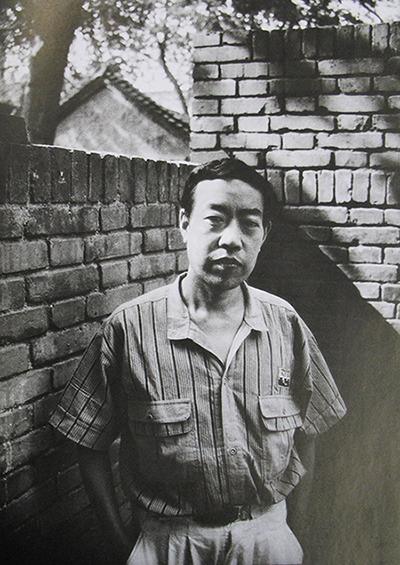

Jia Pingwa, whose given name means ‘ordinary child, ‘ was born in 1952 in Jinpen, a hardscrabble village not far from his ancestral home of Dihua village, Danfeng County, Shangluo Special Administrative Region (present-day Shangluo City), in the Qin mountains of southeastern Shaanxi province.

Establishing a life-long preoccupation with fortune telling, Jia Pingwa’s mother had temporarily moved to Jinpeng at the behest of geomancer. Even so, Jia has described his childhood as having been extremely difficult, with the famines of the late 1950s forcing his parents to send him to live with a childless aunt. In 1966 Jia was finally able to visit Xi’an, one of the countless young children who flooded into the cities during the chaotic first months of the Cultural Revolution . Not long after however, Jia’s father, a Chinese teacher, was accused of being a ‘historical counter-revolutionary.’ Jia to returned to his hometown where was he eventually assigned to a reservoir construction team for a period of three years starting in 1968.

Jia’s father was released in 1970 after four years of imprisonment and forced labor. Despite this bad class background, one year later Jia was given permission to attend Northwest University in Xi’an thanks to his polished calligraphy and strong writing ability.

His first short story, “A Pair of Socks” was published two years later in the Xi’an Daily newspaper, and over the next decade he quickly made a name for himself as an author of socialist realist short fiction for young adults. In the early 1980s, Jia began to experiment with rural fiction, gaining an invitation to join the Xi’an Literary Foundation after the modest success of the 1982 collection Notes from the Highlands. From there his career grew by leaps and bounds, with three more collections appearing over the next four years. His first novel, Shangzhou, was published in 1986, followed by Turbulence in 1988, and Pregnancy in 1989.

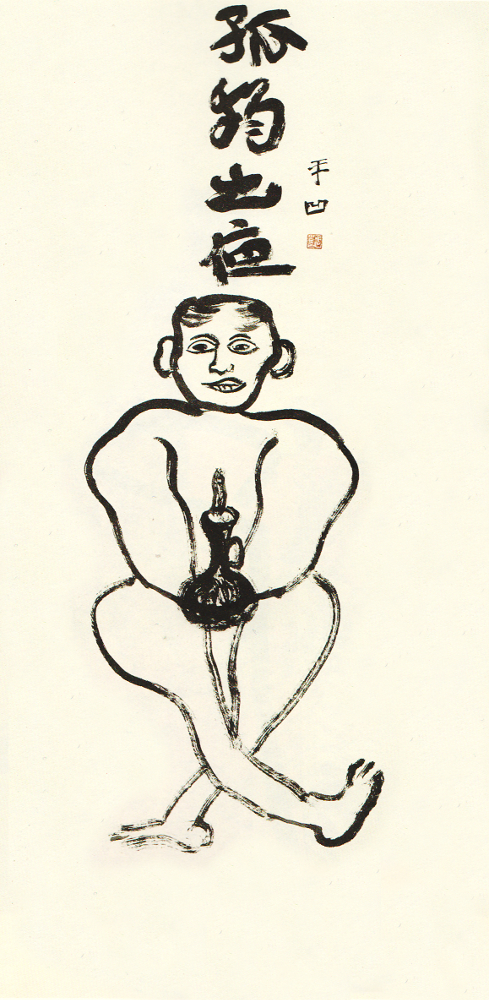

In the difficult period following his father’s death from cancer in 1989, Jia began writing his fourth novel. Ruined City, did not appear until 1993. Although the book was a success, bringing together the notorious 17th century erotic novel Plum in the Golden Vase with Jia’s own lived experience as an acclaimed author of rural fiction, critics largely derided it as pornographic and self-servingly sensational. Three months later, it was taken off the shelves and banned from being reprinted by official publishing channels. This of course only helped sales of the book take off even more, with pirated copies becoming widely available on the black market. Jia, however, struggled with the alternating waves of attention and criticism. His marriage to his first wife fell apart, and he spent several months in the hospital suffering from phantom stomach pains.

The books that followed Ruined City took up many of the same themes, particularly the focus on an individual’s struggle with the society and self. White Nights (1995), Old Gao Village (1998) and Remembering Wolves (2000) stood out from most Chinese novels being published at the time, and can be considered masterpieces in their own right. Shaanxi Opera (2004) was something of a turning point in Jia’s literary output, and has sparked a renaissance, critically and commercially for Jia Pingwa within China. This renaissance is only just now starting to be reflected by the wider availability of Jia’s work in translation.

Until Howard Goldblatt’s 2016 translation of Ruined City (University of Oklahoma Press), the last full length novel by Jia to have made the transition into English was his 1987 novel Turbulence, which was likewise translated by Goldblatt and published by Louisiana State University Press in 1991 (later republished by Grove Press in 2003). This translation won the (now defunct) Pegasus Prize for Literature in 1991, Jia’s first international award. This was followed six years later by the Prix Femina Étranger Prize for Genevieve Imbot-Bichet’s French-language translation of Ruined City (as La Capitale déchue from Éditions Stock, 1997).

Following the publication of Ruined City, AmazonCrossing announced that Nicky Harman had been hired translate Jia’s novel Happy into English, with an expected publication date of October 1, 2017. In Happy, Jia tells the story of a humble trash collector, Happy Liu, chronicling his life in the big city and painting a vivid portrait of the urban-rural divide in contemporary China. Meanwhile, earlier this year the rights to Jia’s 2013 novel, The Lantern Bearer, about an upstanding female village cadre who threads the line between corruption and compassion, were purchased by CN Times Books, with Carlos Rojas signed on to translate.

17 years after Ruined City was banned, meanwhile, Jia was awarded the Mao Dun Literature Prize in 2009 for his 2005 magnum opus, Shaanxi Opera, leading to the re-publication of Ruined City. While Shaanxi Opera deals extensively with rural reform, Jia’s presents the fortunes of the Bai and Xia families as being the result of changes that have taken place over hundreds of years, rather than during the tenure of a particular government. Seen through the eyes of an outcast child, Jia gives readers a visceral introduction to the traditions and social customs of the rural countryside transformed by the relentless passing of time.

In 2011, Jia completed Old Kiln Village, his first work to be set during the Cultural Revolution. Rather than seeking to blame specific individuals or policies, over the course of the long, picaresque novel, Jia provides an account of life in a rural village during this tumultuous time. By the end of the novel, one is left with the sense the more things change, the more they stay the same.

More recently, Jia has taken on the issue of human trafficking in his latest novel, Broken Wings. While Jia has been criticized for his refusal to make sweeping statements to condemn the practice of bride kidnapping, the novel itself presents a grim indictment of both the rural poor and educated urban elites.

As the chairman of the Shaanxi Writers’ Association, Jia is both and insider and an outsider. Having spent much of his life depicting the decline of rural life in his home province, Jia finds himself at odds with an increasingly urban contemporary society, and it is with his fellow discontents that he finds his most fervid readers. Writing long, difficult, and ambiguous novels, Jia eschews easy answers in favor of digressions and doggerel. His writing provides an important window not only into a culture at the crossroads, but the human condition itself.

Writing Style

Framing Jia Pingwa’s work within a context that can been understood by Western readers is a challenging task. One author who is often compared to Jia Pingwa for a similar focus on rural themes and ‘earthy’ language is Mo Yan. When Mo Yan was awarded the 2012 Nobel Prize, his writing was described as “hallucinatory realism [which] merges folk tales, history and the contemporary,” drawing a direct comparison to the work of Columbian author Gabriel Garcia Marquez.

At the same time, the award was criticized by a number of scholars and human rights activists who singled out Mo Yan’s selective treatment of history and his willingness to use “daft hilarity” to gloss over the darker side of central planning disasters such as the Great Leap Forward, in which as many as 30 million people are believed to have died.

Perhaps befitting a writer that got his start in the late-1970s in China, Jia on the other hand seems to be more of a socialist realist than a magical realist—although Jia makes liberal use of bawdy humor, his work is possessed with an overwhelming sense of tragic loss rather than the carnivalistic excess of Mo Yan.

This means that although, like most writers in China today, Jia steers clear of direct criticism of specific government policies (for example, the one child policy is never discussed in Broken Wings), one can find a long running thread social criticism in his work regarding the widening divide between the urban and rural, the cultured and uncultured.

This thread has a surprising origin however, not in the social activism of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests, or even in the symbolically-linked May Fourth protests of 1919, but instead in his personal experience of alienation moving between countryside to the city. Again and again, when facing controversy, Jia has fled to the countryside—but it is the city where he has found fame and fortune.

As the leading English-language scholar of Jia’s work, Yiyan Wang has pointed out, unlike many writers that turned their attention to the countryside, Jia is actually from the countryside, giving Jia’s writing on rural Shaanxi a markedly different tone from anything written by author. By the time the “roots-seeking” writers of the ’80s and ’90s were discovering what they imagined to be the foundation of traditional Chinese culture, Jia Pingwa had fled to Xi’an and was exploring the mind of a man trapped in a nation and a city that had been smashed—Zhuang Zhidie, the quixotic protagonist of his early masterpiece, Ruined City.

In many of Jia’s works, one gets the sense that no traditional culture remains to be found, that which does remain has been so devalued that it isn’t worth finding. Returning to a rural setting after novels of the city, Jia’s love of rural life, his knowledge of village life and his roots in rural Shaanxi shine through.

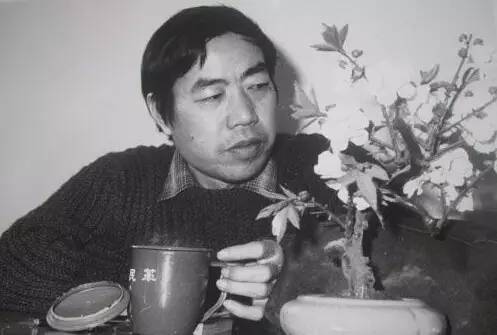

At the same time, as the son of school teacher who instilled in him a respect for the classics early on, Jia is much more indebted to older Chinese literary forms than anything from the West, or even among his contemporaries. His books abound in classical allusions, particularly to Ming vernacular novels such as Dream of Red Mansions / Story of the Stone and the erotic satire of Plum in the Golden Vase, making Jia one of the rare examples of an author who has succeeded in making the old new again.

There is little reason to fear that being unfamiliar with these works will stop readers from enjoying of his novels, however. If an Anglophone reader wants to go deeper and track down a particular allusion, they certainly could, as there is ample English-language scholarship on the literature of this period. For the vast majority of readers of course, most will simply breeze overhead or remain buried only to be uncovered on a second or third re-reading. More important are his rich casts of characters, complex narratives, and subtle social satire.

The closest cousins in Western literature to Jia’s longer works, such as Shaanxi Opera and Old Kiln Village, are arguably modernist tomes of the late-19th and early-20th century. Even Jia’s shorter novels are populated with countless characters floating through, suggesting that Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury might be a good comparison — sprawling narratives centering on the decline of aristocratic rural families and idiosyncratic narrators are obvious parallels.

Also like Faulkner, and Mark Twain, who Faulkner considered “all of our grandfather,” Jia also shares a biting wit and love of a good story. Much in the same way that few critics would argue that The Sound and the Fury or Huckleberry Finn represent a radical critique of the American government however, the social criticism in Jia’s novel primary takes aim at the vagaries of human nature and the fate of the downtrodden.

Thematically then, one can also see elements of the work of more contemporary ‘outsider’ American authors such as Hubert Selby Jr., Cormac McCarthy, Bret Easton Ellis, Chuck Palahniuk, and James Ellroy. Like Selby’s Last Exit to Brooklyn, Jia’s work is deeply cynical but also deeply rooted in true stories of grinding poverty and desperation. Like McCarthy, Jia favors lawless, post-apocalyptic wastelands (both literal ones, like the draught-parched Shaanxi countryside, and figurative ones, such as the cultural wasteland of Ruined City).

The sanity of Jia’s protagonists can never be taken for granted, but where Ellis and Palahniuk lampoon 20th century consumerism which drives urban and suburban madness in their respective novels American Psycho and Fight Club, Jia instead skewers the uniquely Chinese obsession with tradition and classical erudition, which seem all the more absurd when placed in the mouths of his wretched and reviled protagonists.

Finally, like Ellroy in novels such as The Black Dhalia and My Dark Places, Jia often draws on the deep undercurrent of autobiography and personal anxiety which animate his work, often including characters who seem to be thinly veiled versions of the author of himself at various stages in his career. This sense of autobiography is reinforced by the essays Jia is appends his novels with. Describing the deeply personal events which informed his writing process, these essays touch on everything from the death of his father to the chaotic violence of the Cultural Revolution to the kidnapping of a young girl from his hometown.

Despite this, in common with many controversial, yet celebrated, authors, Jia rarely moralizes or explains his work directly, a tendency which has earned him his fair share of detractors.

For his fans, Jia is a larger than life figure who sits outside the literary tradition, having become something of symbol for the hyper-masculine, outsider autodidact within Chinese literary circles. His lack of polish is reflected in his refusal to speak standard Chinese, saying, “The common tongue is for common people.”

Likewise, Jia has been scorned for writing long and difficult to follow run-on sentences. Unlike many Western authors like McCarthy, who draw inspiration from James Joyce’s modernist flow of consciousness writing, Jia’s inspiration (like Faulkner, Twain, and Selby before him) is closer to home, in conversations between friends and neighbors overheard while growing up in his native place.

Most troubling of all for his detractors, Jia doesn’t shy from graphic depictions of sex and sexual violence. In particular, Ruined City has been criticized for the male-centered narrative, in which women have very little agency of their own, beyond satisfying male pleasure.

Jia’s most recent novel, Broken Wings, which is told from the perspective of a trafficked young woman, would seem to be Jia’s attempt to respond to this lack of female perspectives in his work to date, but it has drawn criticism for its treatment of rape and trafficking.

To compare Jia’s work to McCarthy’s again, the crushing futility of the protagonist’s efforts to escape from sexual slavery and domestic violence, is every bit as dark as anything from The Road, but like that novel, poignant flashes hope and joy stand out in the midst of overwhelming darkness. (This is of course in contrast with Selby, whose work is just plain crushing.)

While some parallels to Ellis and Palahniuk’s dark humor and twisted storytelling might be seen in Jia’s work, meanwhile, overall it seems less glib, relying more on the cues of Chinese opera and vernacular fiction than on the smash cuts of film and television.

For translators and for publishers alike, Jia’s work represents an opportunity and a challenge. While Jia’s work has already received ample attention from academics writing in English, his two translated novels have largely failed to attract the attention Anglophone readers and critics.

One exception is M.A. Orthofer, of the online literary journal The Complete Review. Shortly after Ruined City was published in January, 2016, Orthofer wrote:

The pacing of Ruined City isn’t like that in most contemporary fiction. It putters along and the action can seem limited, even inconsequential. It takes up different threads, and leaves characters out of sight — and grasp — for extended stretches, the focus not on what one imagines is the central story, but rather on the incidental. Even when things come to a head in a courtroom, Jia keeps his distance, preferring to summarize second-hand. It takes a certain kind of patience to read this kind of often pedestrian-seeming narrative, and the payoff may well not be sufficient for many readers. But in its sum Ruined City is also a powerful, ultimately even devastating work — a striking success.

‘Devastating’ is certainly a word that comes to mind when reading Jia’s work, making the most difficult part of translation often not the language, but the overwhelming sadness that comes across during his most moving passages.

At his worst, one gets the sense that Jia is meticulous chronicler of human misery. At his best, however, one feels that Jia is not so much fetishizing of violence and rural poverty, as he is facilitating the gradual release from suffering that comes from of achieving a higher plane—a neo-Buddhist meditation on the guts and gore and bones of late-stage capitalism in post-communist China.

Steeped in the classical and historical Chinese tradition, the world-view that Jia presents in his work is a never-ending cycle of growth and decay, consolidation and diffusion. Jia leaves his readers changed, which for many is an unsettling experience. I would argue, however, that it is a necessary one.

– Nick Stember, December 2016. An earlier version of this essay appears in Chinese Literature Today, Vol. 6, 1. It is reprinted here with permission of the author.